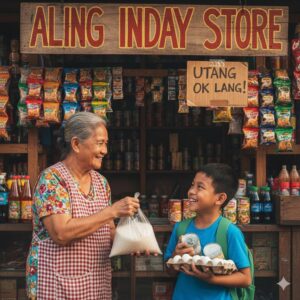

SA SOBRANG KAHIRAPAN NG BUHAY AY NAGAGAWA KONG BOLAHIN SI ALING INDAY PARA AKO AY MAPAUTANG NYA GAMIT ANG KAGWAPUHAN NI ITAYSA ARAW…

Naku po, mga Ka-Chika at mga kababayan, mukhang hindi na talaga matatahimik ang pangalan ni SAGIP Partylist Representative Rodante Marcoleta sa mga balita…

Para sa marami nating mga kababayan, lalo na ang mga nasa edad 60 pataas, ang gabi ay hindi na panahon ng pahinga kundi…

Sa paglipas ng panahon, isa sa mga pinakamalaking hamon na kinakaharap ng maraming Pilipino ay ang unti-unting pagputi o pag-uuban at ang nakakaalarmang…

Ang pangalan ko ay Hạnh, dalawampung taong gulang ako. Mahirap ang aming probinsya. Maaga nang namatay ang aking ama, at mag-isa kaming pinalaki…

Sabi nila, ang kapangyarihan ang nagpapakita ng tunay na kalikasan ng mga tao, ngunit may natutunan si Elena Valenzuela na kakaiba sa paglipas…

Ako si Nico. 32 years old. Gwapo, matipuno… o hindi ko alam kung matatawag pa ba akong ganun sa itsura ko ngayon. Dati,…

Isang oras bago ang kasal ko, narinig ko ang bulong ng fiancé ko sa nanay niya, “Hindi ko siya mahal. Pera lang ang…

NAGKAROON AKO NG KATULONG NA MASAYAHIN PERO SA LIKOD NG KANYANG MGA NGITI AY MAY NAKAKUBLI PALANG KALUNGKUTAN NA SYANG NAGPABAGO SA AKING…