A retired rancher had lived in solitude for years until five beautiful but exhausted Apache widows came to beg him for refuge on their ranch…

By the end of November 1882, the wind was already bringing frost earlier than usual. High in the Silverbuds Hills in Colorado Territory, Reed Callahan had already covered the windows with oily cloth and piled up the last loads of firewood. I didn’t expect visitors, I never expected them. The nearest town was almost 20 km down rock and snow.

The nearest neighbor had died in the spring. The cabin stood isolated against the hillside built by Reed’s own hands 6 years ago, when he decided to leave the company of men behind and keep his animals. Reed was 32 years old. Before dedicating himself fully to the ranch, he had worked as an interpreter.

He was a Spanish and Comanche dominabache and was hired by promoted when they wanted agreements without shedding blood. But he saw too much blood anyway. He had witnessed young women fall under tangled bullets, children torn off and put on carts, old men lying on the ground barely covered by their blankets.

And when he tried to speak, no one wanted to listen, so he left. Since then, silence was his only company. That afternoon he was splitting logs behind the hut, thick fir, still wet, made of resin. His gloves were torn at the toes and his boots had a crack in his left heel.

He struck steadily, not for exercise, not to distract himself, simply because the winter would be long and the fire would devour quickly. A pot was boiling on the stove and a piece of goat meat was waiting to become a stew when the silence changed. It wasn’t wind, the sound was even. Rit stopped mid-slam and shook his ear.

Steps, several, light, cautious, human. He put his hand around the side of the hut near the revolver he carried in his belt, but he had not yet drawn it. As he turned into the porch and past it near broken logs, he saw five women standing at the edge of the clearing in the snowy undergrowth. They had no horses or wagon, only their feet reddened by the cold.

Wrapped in rags, they wore dresses that were once leather or cotton, now patched, torn and hardened by frost. They wore blankets slung over their shoulders, barely covering what was left of their decorum. One of them was the one in front, with a full body, dark hair, tied up with a tendon loop. He took a step forward, his mouth dry, but his gaze steady.

Re didn’t move. The woman did not plead. He spoke directly. We need a place. Just one night we didn’t order more than that. Re looked at her, then looked behind her. He saw what he didn’t say. The youngest had a blood stain running down her thigh. The tallest one held her arm as if it were dislocated.

Another was barely carrying a small cloth backpack. They were not wanderers, they were survivors. Reid looked up at the trees behind him. Nothing moved. There were no patrols, there were no horsemen. He remembered the last time he let someone in. Three years ago, a trapper fleeing debt.

He drank his reserves, stole his best horse, and left him tied up in the barn for a day and a half. But these were not men, they were Apache widows, you could tell in their posture, proud, half savage, not defeated, only worn out. Reh opened the gate of the fence, said nothing. They entered one by one slowly, watching him as they passed. He smelled the smell of blood and pine needles on her clothes, one of them larger than the others, tall hips, wide wrinkles, waves on her face. He did not thank him at the time. Inside the fire was already low.

Rid threw in one more log, moved the pot, and grabbed a bowl from the shelf. He poured out what was left of the previous night’s stew, thick with roots and meat, and passed through the dishes without comment. They settled in a circle near the fire. The one who had spoken remained on her knees, her palms extended towards the heat. Her dress was torn at the chest. He noticed the cut.

It had once been cooked, but it opened again. The sun-tanned skin underneath was damp with cold sweat. She didn’t hide it or seem to care. Rid’s throat tightened. It was not desire, it was not shame, but anger. Who did he do that against? The younger Tala, although he didn’t know her name yet, trembled as she drank. He made no noise, he didn’t cry, he just swallowed silently with his eyes open and exhausted.

They had not come in search of alms. They came because there was no other place. After dinner, Rid gave them folded wool blankets. He did not ask for names, nor did he try to talk. This does not win the trust of those who have been persecuted.

He took a couple of extra cots from a trunk and arranged a place by the stove. The ground was hard, but less icy than outside. he put the last blanket near Sayin. She looked up at him without fear, just evaluating. His eyes went over his face, his posture, his belt. He knew that he was armed, that he lived alone, that he could do whatever he wanted, but he didn’t.

He simply stepped back and sat by the window, his rifle on his legs, watching the darkness in case anyone had followed them. Behind him he heard them settling down. One of them began to whisper in a soft, breathy tone. Another let out a brief low laugh. Sayin replied something and then silence. It sounded like home or one’s memory. Re didn’t sleep that night, not at all.

He looked at the door, heard the crackle of firewood and tried not to think too much about the fact that five strangers had entered his house and he was not afraid. No, it really was something else. Responsibility. It weighed on his chest as hard as snow on the roof, and he did not throw them out. The morning came quiet and sharp.

Reh was already awake before the sun peeked over the mountains. He had slept in the chair with his boots on his lap. His neck hurt, but he didn’t stretch. First he listened. Inside, the five were still asleep, wrapped in blankets, breathing evenly through the fire reduced to embers. One of them, chirping loudly and with a hawk-fairy gaze, rested by the door as if standing guard.

Such a young woman was curled up in a ball, her face buried in her arms. The others were lying on the floor between wool and the few rags they carried. Re put down the rifle and went to the stove. He slowly lit the fire carefully and added water to the pot. His hands moved without thinking about it, a habit older than fear.

When the first light stained the boards, Sayin sat up on one elbow, his hair loose around his neck. The wrinkled suede dress still torn at the chest. He did not cover up. I watched him without shyness, without insinuation, just measuring. He held her gaze and nodded briefly. She got up. They did not speak. Red handed him a can of coffee. She understood, measured the portions without asking.

By the time the others woke up the smell of coffee, it filled the cabin. The steam from the cups rose like winter breath. Again they ate goat stew. No one complained, not even the youngest. After breakfast, Sayin left without saying a word. The others followed. Rit stood by letting the door close. From the window he watched them. They moved with intention.

Sayin checked the Silv goats’ pen once to see how they responded. Kaya lifted a torn blanket from the railing and sat down to repair it. Paya circled the hut, watching the hills as if waiting for someone. Noli dragged a bucket to the well without anyone asking. Tala stood with his hands in his mouth blowing hot air against the cold.

They were not invited, they were survivors. And the survivors do not stand still. Rit went out and broke wood again. Sayen accompanied him shortly after. He didn’t ask permission, he just picked up splinters and piled them up next to the wall. She moved slowly, at a pain, but stubbornly. Her dress clung to her legs when she bent over. The snow wet the fabric.

The opening on one side was wider, showing more skin than he might have noticed. Or maybe she did, but Son never looked at her. He didn’t need to. Noon arrived. The sun barely warmed the earth, but it removed the frost from the roof. Inside, Rid took out what little was left: flour, salt, butter and a piece of dried meat.

He sat down at the table and watched as Nolly and Kaaban cooked. One kneaded the other cleaned the surface. No chatter just rhythm. He leaned back with his arms crossed. The questions piled up. Who were they? Where did they come from? Why now? He didn’t say them out loud, but in the afternoon Sayin stood at the entrance while the others worked and finally blurted something out at him.

We come from below Fort Garland, he said. There was an assault. Some drunken white ranchers thought we were hiding warriors. She looked him in the eye. It was not true. Reed was silent. Only the face marked on the 100 looked at her. The neck with old scrapes. “Most of us lost our men months ago,” she continued, but they don’t care. “Widow or not take what they want.” Redit didn’t respond right away.

There was no pity on his face, only understanding. “They burned down our shelter,” she said. “They took what little we had. We walked five days.” Redit looked down. Five days in that snow. Without shoes, Sayin took another step inside. We saw your smoke.

From the hill we thought that a man lived alone here, but we would not have risked it any other way. He looked at her for a few seconds. Did you guess right? Answered. She gave a minimal smile and then erased it. We won’t stay long, just long enough to walk again. To that Reid did not reply. That afternoon he took extra hermientas, an axe, nails, rope from the shed.

He didn’t explain anything, he just left them there for nightfall. Pay had already repaired the back door. Kaya mended a torn curtain. Nol adjusted the bolt and Rid surprised himself on the brown porch in hand, watching them move as if they had always belonged there. None of them asked what they expected from them. None of them listened to rules.

Sayin walked past him entering the house. His hip brushed his knee. It was not an accident, but neither was it entirely intentional. Their eyes met again. That night the five of them slept inside. The blankets were arranged closer to the stove. Tala huddled next to Calla. Paya stood in the doorway again, his arms folded over his chest. Noli lying on her back.

Eyes open in the dark. Sayin took the far end near the chair where Reed sat back. She didn’t fall asleep right away. He lay on his side, looking at him. “I know what men expect,” he murmured. Re said nothing. I know what people will say if we stay too long. Still, he remained silent. She examined his face, the scar next to his eye, the stiffness in his shoulders.

She nodded to herself and turned around. Rid stood for a long time looking at the door, then the fire and then the silhouette of his back under the blanket and for the first time in years he didn’t feel like he was watching anything, he felt like he belonged and he didn’t kick them out. That night the snowfall was heavy, covering the earth in a white silence.

In the morning outside everything was still, without wind, without footprints. No noise. Just piles of snow and a low gray sky that wouldn’t let up. Inside the air felt warm, but tight. The fire had been consumed. The smell of boiled coffee wafted around, the wood clicked slightly, no one spoke yet. Re was at the table sharpening a knife. The sound of the wet, slow, rhythmic stone marked his breathing.

On the other side, Sayin was by the stove. adding more water to the pot. Her dress stuck to her legs wet from having stepped out onto the porch in the snow. He didn’t ask permission before leaving, he just took the bucket and came back with it full. The others moved in silence. Calla swept near the home. Tala folded a blanket.

Paya alertly checked the window looking for drafts. Nolly was standing by the door. Arms crossed. as if doubting if it was safe to go out again. Sayin spoke first. You receive visitors from the village. Reid didn’t look up. She waited. Someone brings you supplies. I go down once a month. Now he did look at her. Not until after the decielo. She nodded slowly. That clarified everything for him. No one would come to check.

There would be no surprises. If something happened there, no one would know until spring. He went back to the stove. Rid noticed how she moved to a sore but strong one. In his shoulders there was tension, not tiredness. She was not a woman recovering from rest. He was someone who hadn’t had him in weeks, maybe months.

When breakfast was over, Red pulled a map out of the trunk next to his bed. he unfolded it on the table. It was old stained with oil and rain with worn edges. He pointed to the valley below Silverbut. There is a trail to Carsonfork. You follow the river to the south. There you will find some stalls. Sayin approached.

Do you want us to leave? He held her gaze. I’ll show you the way in case they still plan to leave. She rested her hands on the edge of the table, so close that her fingers brushed the edge of the freshly sharpened knife. “We would have kept walking,” he said. “But the youngest.” He pointed lightly to Tala, who was standing by the fire tying a rag around his foot. “He can’t anymore.

The wounds are older than we told you.” Red looked towards Tala. The canvas was stained with blood. The girl caught him watching her and pulled her dress down, covering her legs in embarrassment. Red turned his eyes to Sayin. I have a story. It’s not much, but it will do. Sayin nodded. We will work to pay for it.

I didn’t ask you. She stared at him. I don’t offer it for you, I offer it for her. Red didn’t argue, he carried the jar and sat on the ground next to Tala. She shrank, but he didn’t touch her, he just opened the can and put it next to her knee. “You do it,” he said quietly. “Just keep it covered afterwards.” Tala looked at him once, then picked up the jar. Pia, on the other side of the room, stood behind her, watching Red.

He said nothing, but a slight relief appeared on his face. That afternoon the cabin was filled with quiet movement. Ka asked for a needle and thread. He repaired Rid’s jacket by carefully sewing the shoulder seam. Noli cleaned the shelves. Tala rested. Sayin stayed outside most of the time. R.

He heard the axe strike again. Once, twice, he got up and stepped out onto the porch. She was splitting splinters by the shed, her breath coming out in clouds. Her dress was soaked from kneeling in the snow. The tear in his chest remained unrepaired. She fell loosely, revealing more than she should. She didn’t realize he was looking at her or didn’t care.

Rit walked over and placed a new log on top of the stump. “That blade is very light,” Sayin said. Growled. Serves. He handed her a heavier axe. She took it just by the grip and lowered it clean and strong with the practice of those who do it to survive, not for pride. He nodded. You’re from White Mountain. Sein stopped with sweat on his neck.

He didn’t respond closely to Forch breaking down. Her way of speaking, her bearing, was not that of tribal nobility, nor of a peasant wife of the Valley. Something in between. She looked at him. You worked with the military once. They sent you here. I didn’t leave. She didn’t ask why. That was what he told Rid that he already sensed it. They finished leaving and entered with the firewood together.

That night it snowed again. Rid cooked fresh meat for a married rabbit days before. He didn’t add herbs that he had gathered near the shed. The aroma warmed more than the fire. After dinner the room was calm. It was not a heavy or uncomfortable silence. Sayin settled down by the fire. He stretched his legs, a bent knee.

The tear in her dress moved when she turned, revealing part of her thigh. Reid noticed it, but said nothing. He didn’t stare just once, and looked away. She watched him without shame, without offering herself, only checking if he would move away. He didn’t. Later, when the others were asleep, Sayin got up and poured some water.

He didn’t drink, he just held her standing on the threshold between the light of the fire and the shadow. You’re not like everyone else,” Red said, not moving from his seat. “I’ve met quiet men,” he continued, and patients too. “But most sooner or later expect something in return.” He held her gaze and Tusayin stared at him for a while until his face softened.

I don’t know what I’m waiting for, he said at last, but I’m not afraid. She stepped forward close enough for him to feel the warmth of her body. The dress clung to her curves, the chest rose and fell evenly. Her face was marked by the journey and the smoke, but there was beauty there. Not a fragile beauty, but stubborn gained. Red didn’t touch her, she didn’t say anything.

She remained a moment longer, then turned and returned to her place. He stared at the fire, he didn’t know if what was growing was trust or temptation, but he didn’t want them to leave, not a single one of them, and that thought scared him more than he would admit. The next morning, Reid woke up earlier than usual.

He hadn’t wanted to fall asleep, but at some point the fire went out and the cold caught up with him. The thick smoke had lingered in the air. He sat up in the chair by the stove, craned his neck, and looked around the cabin. They were all still there. Sayin was curled up on her side, her face turned towards the embers. Paya, as always, slept near the door.

Kaya had moved in her sleep with her arms outstretched on Tala’s legs, as if protecting her. Nali rested on her back, her hands folded on her chest. None of them moved. Reed sat up slowly, walked over to the stove, and stoked the fire. His gestures were silent, but as he poured water into the pot, he heard it rise.

He stood beside him quietly so close that his shoulders brushed. His voice came out low. I thought you’d be gone when we woke up. I don’t stray far. She looked at him. You always stay on the shore as a separate. He did not answer. Outside it was still snowing. Of that snow that does not stop until it covers everything. Sayin poured two mugs of coffee and gave him one.

He didn’t ask for permission, he just put it in his hand as if they had done it 100 times. Reid drank and finally asked what he hadn’t said before. You mentioned that bounty hunters attacked his shelter. What happened next? Sin took a sip. They arrived at night. They said they were looking for two men who stole horses in cannon shots. There was no evidence, only weapons and liquor.

His jaw hardened. They hit Pia first. They said he made fun of them. Then they took Nali’s bag. We had little food. They still took her. Redit looked at Nali, still asleep. His face now calm, but with a faint bruise under his eye. They burned everything, Sayin added. They didn’t kill us. They said we were lucky.

They were not with a tribe. She shook her head. No tribe welcomes a widow without status. And we no longer had men to speak for us. Re nodded slowly. It was something I understood better than anyone. In those lands, protection did not come from the law, but from those who were by your side. After breakfast, Rit went out to check the traps. Snow covered the valley, but the sky was getting clearer.

He followed the path to the stream. He caught a rabbit, a squirrel enough for a stew or maybe a roast if they rationed it. He returned before noon. As he climbed the hill he stopped. The cabin didn’t look the same anymore. There was smoke from the chimney and another column behind the shed. He quickly advanced his hand near the belt. Attentive eyes, but it was not dangerous.

Sayin had raised a second stove and around it the women worked calmly in coordination. Noli was boiling rags in a tin bucket. Calla cleaned rabbit skins with a bone scraper. Tala was wrapped in blankets by the fire. The bandaged foot firmer than before and on his lips a slight smile as he watched them.

Kaya sat up when she saw Rid, but she didn’t say anything, she just nodded. At the back, Rid approached Sayin, who was splitting wood next to the pile. You put it together quickly, he said. We don’t want to spend your food or your firewood. We plan to cook outside when the weather permits. He handed her the newlywed rabbit. She looked at him in surprise. You didn’t have to do that. You didn’t have to stay, either, he replied.

That night they had a better dinner than before. Rabbit stew with a little ground chili quesay. She took it out of a small bag hidden under her skirt. It was the first time they all sat down together at the table. There weren’t many words, but when Nol laughed softly at something he said in Apache, it didn’t sound bitter, it was soft, light, and Rid felt a different breath in his chest.

Later, with the dishes washed and the floor clean, Jin sat there while the others went to sleep. He waited for Rid to approach the stove again. Are you still waiting for us to ask for more?” he said. He turned to her. No. Yes, she answered bluntly. Do you think that sooner or later we will abuse this? That we will claim your bed, your food, your life? Re looked at her. I don’t think that. So, what do you think? He didn’t respond right away.

She got up, walked until she was in front of him. The light of the fire illuminated the scar on her lip, the curve of her neck exposed by the torn dress that she never repaired. “I know what men see when they look at me now,” she said. “I know what they want.” Rid’s throat closed, not out of desire, but because of something older, deeper.

“I’m not like them,” he murmured. “I know,” she replied. “That’s the problem.” They were so close that the air became dense. She raised her hand a little and rested it on her chest. His fingers were cold. His heart beat steadily under his palm. Rid didn’t move, but he didn’t push her away either. She leaned over slowly and kissed him. It was not rushed. He was not shy.

His mouth was warm, patiently looking for him. When he retired, he did not explain anything. He did not ask for forgiveness. he just whispered goodnight and went to his room. Re remained motionless. He didn’t sleep for a long time, but for the first time he didn’t guard the door. He heard his breathing rise and fall from his chest and felt that perhaps at last he did not expect to be alone again.

The following days passed slowly, but full. The snow came a little. The wind was still cutting in the mornings. But the sky opened wider, and the light lasted until after dark. That gave the cabin and those who lived inside a rhythm. Waking up, working, warming up, sleeping and in between something quiet began to settle down. It was no longer just about surviving, it was about existing.

Sayin did not speak of the kiss again. Neither did Rid, but something had changed. She moved freer now closer, more intentional in how she stood next to him, how she passed the tools to him, how her fingers brushed against her arm and stood for just a moment saying, “I remember. He didn’t force me. I see you.” And Rid did not turn away.

She didn’t talk more than usual, but every time she passed by her eyes followed her for just a second. Every time he went out, he turned to see if he was watching him. Often it was. That morning Rit rode into the low pass for the first time in weeks. I needed to go out and check the traps that ran near the forest of Álamos. He left before dawn.

The others barely moved. Sayin was the only one who held his gaze before he left. She didn’t ask where he was going, just held her coat while he put it on and then quietly adjusted her collar. Re went out with the sun rising behind him, cutting through the snow with golden light.

By the time he returned in the early afternoon, the cabin looked different. Smoke kept coming out. The shed door was patched. The firewood was stacked neatly against the wall, but there was something else in the air in the silence. He felt it before he saw it. Something had happened. He got off his horse, looked around the yard.

Then, the door opened or opened. Pia was in the frame. Arms crossed. “We had a visit,” he said. Reid clenched his jaw. Who? A white man. Thirty-something. He had an adjutant’s star, but no horse. He said he came from the village. He did not claim that it passed from Wolf Hollow. He assured that he was looking for two stolen mules.

He walked past her and toward the cabin. The others were sitting. They all looked calm, except for Tala with red eyes. I had cried, but not anymore. Sayin stood by the window, arms folded. He didn’t come for mules,” Sayin said. He saw us among the trees. He began to ask where we were from, if we had papers. Reed’s voice came low. He touched them.

Sayin shook his head. He asked why we were here. He said that we should be under someone’s authority. What did you say that you were our boss who cooked and cleaned for a roof and bread, that we were not prisoners, that he could go on his way? Reid looked at the table. A ring of melted snow marked where he had left a cup. Your cup.

Red went out onto the porch, scanned the trees with his eyes. Nothing moved. There were no fresh footprints on the fence. The wind had erased them or someone swept them away, but the feeling did not go away. He spent the afternoon outside splitting firewood, watching the hill with a hard look. Sayin approached shortly before nightfall.

He didn’t speak right away, just leaning against the post next to him. “We should go,” he said at last. Rid didn’t answer. She blinked. It could bring more men, more questions. If I was going to. Rid replied. He wouldn’t have come alone the first time. Sin crossed his arms. Do you think we are safe here? I think here more than out there. She was silent for a moment.

Then Tala became nervous when she asked her name. She froze almost and cried. He saw it. She saw that she was scared. He lied pretty quickly, but he shook her. He is young. Red said, “Yes. And they have married her before. And they have married her before. Sayin turned to him. She is not the only one. Rid nodded. I know. That night the fire burned more than usual.

Re lay awake near the door. Pia also stood up sharpening a knife. Sayin was resting by the window, his eyes open. No one said it, but the whole cabin felt it. The outside world had already seen them. They were no longer invisible. But still no one fled. The next morning, Red took Tala with him to the shed. Just the two of us.

He showed him how to adjust the door bolt, how to set traps, how to read signs in the snow, broken branches, footprints, changes in the wind. She spoke little, but her hands stopped shaking. Returning inside, Tala looked at Sayin and gave him a slight nod. Later, while the others cleaned furs and sewed Red and Sayin stitching, they came out behind the hut. She handed him a cup of boiled root tea. He took it.

“I was wrong,” she said. “In what?” “Thinking we’d be a burden if we stayed long.” They were not. She looked at him carefully. “And now we are? Red didn’t answer right away, leaning over slowly and carefully brushing a strand of hair from her cheek. Then, in a low voice, he said, “No.” She came over and kissed him again.

It lasted longer this time. Neither of them turned to see if anyone was watching them. And this time she didn’t walk away. Then she stayed with him. His hand in his coat pocket, his shoulder against his arm, the two of them looking at the forest in silence. It was already the end of December when the snow fell thicker, heavier and wetter, covering the earth up to the waist, the cabin became a fortress, not by choice, but by necessity. For three days no one came out.

Firewood had to be rationed, goats inside the shed, water melted from the snow, meals were lengthened, no one complained. Inside, the women worked without pause. Paya built a frame next to the stove to dry wet boots. Calla boiled herbs kept in bundles tied with string.

Its fresh and pungent aromas broke the smoke. Nali patched the ceiling from the inside with scraps of leather. Tala rested more, the wound on his foot almost closed. Now he spoke more fluently. Not long sentences, but long enough to ask where Rid kept the sugar or if he could stoke the fire. Sayin remained close to Rid.

They didn’t share a bed, not yet, but they shared a rhythm. They split wood shoulder to shoulder. He would pass her a coat when he saw her shivering. She would wipe the snow off his back when he came back from the shed. At night he sat closer. their knees rubbing under the table. His hand sometimes rested on his thigh for just an instant like a wordless promise.

It was on the fourth day of snowfall that the question that was silently hovering was finally said aloud. Nali did it. She stood by the table after dinner, wiping her hands on her lap, her eyes fixed on reed. What will happen in spring? The fourth fell silent. The pot was still yumming in the center of the table. Sayin looked at him. Pia stopped tying a loop to the rope.

Ka stood still. Reid didn’t look away. What do they want to happen? Asked. Nali’s voice did not tremble. That Wolf Hollow man can come back. Others too. We are five Apache widows living in a white man’s house. Even if you haven’t done anything wrong, they won’t see it that way. Sayin intervened. He has done nothing wrong. None of us have.

But the law doesn’t care, Pia said coldly. Rid leaned back on his chair, the wood creaking under his weight. I know what the law says, he replied. And I know what the earth dictates. No one here survives the winter if they don’t work together. In spring we will show it as it should be. Sayin’s sign frowned. Có Rid looked at her and then at all of them.

I have paper records. I could write that I have taken five helpers on my ranch. Five iron hands all legal, all registered. Pia raised an eyebrow and the people will simply believe it. They don’t need to,” Rid replied. That it is written and sealed is enough. No one watches closely unless they are looking for a lawsuit.

Sayin stared at him. Would you do that? I’ve already done something worse, remember? His eyes met hers. I let them in. That prompted a short laugh from Nolly, then another from Calla. Even Pia showed a slight smile. Sayin didn’t laugh, but she got up, walked up to him, and kissed him in front of everyone. It wasn’t long, it wasn’t to show off, just what was necessary.

That night, when the fire died down and the others were asleep, Sayin remained next to Rid, did not return to his blanket, stayed behind his chair and slid his arms over his shoulders, resting his cheek on the back of his neck. He raised his hand, touched her forearm. None of them spoke. Then she moved forward, kneeling between his legs. The ripped suede dress still clung to her wet curves.

His chest rose slowly. The open collar worn by work and use. His skin was warm despite the cold. His thighs scarred by days of kneeling, working, surviving. She leaned over and kissed him again. This time it went deeper. He took her hands and guided them by putting them where she wanted. On her hips her waist, her back.

Reid didn’t hurry, he didn’t hold her roughly, his caress was firmly contained. Her breathing became heavier. He settled into his lap, squeezing tighter, still speechless. They made love in silence, without bed, without ceremony, only skin to skin, warmth shared under the light of the fire and breath in the darkness. When he finished, she was curled up against him.

His hand was open on her chest, his cheek on her shoulder, and for the first time he held someone with both arms, not to save her, not to protect her, but to keep her. The storm was raging outside, but inside they had built something firm. At dawn, when the snowfall came and the light came through the cracks, no one spoke of what had happened, but the air had changed. They were no longer just weathering the winter, they were now surviving together.

and none of them thought of leaving. The first clear morning after the storm came in hard and bright. Rays of light cut through the piles of snow like blades drawing edges on the target. The wind had died down. Snow surrounded the cabin up to its chest in places.

The road to the well was buried, the roof of the shed given on one side, but inside the warmth was maintained not only by the fire, but by the proximity of something that was finally taking root. Sinin woke up in Rid’s room. They had quietly parted before dawn before the others opened their eyes. He returned to his blanket with calm steps and calm breathing, but the change was felt.

Reed didn’t try to hide it, nor did she. No one asked anything. That was the language they already shared. Silence as respect. By mid-morning they were outside clearing snow. Rid shoveled from the porch to the shed. Paya was breaking the ice on the ceiling. Kaya and Nali cleaned the pens. Felling without a bandage for the first time in days limped along the path that Rid had opened, carrying a bucket with both hands.

His face red from the cold, but with a discreet smile. It was Sayin who noticed the footprints first. He was near the north fence removing mud from the base of the post when he saw them. Fresh, deep footsteps, not of them. He didn’t scream. He returned to the porch and sought Red’s gaze. He understood her face before she spoke.

They walked the property line together. They found the trail near the trees. Whoever had come from the south made a wide turn and withdrew. He didn’t go to the cabin, he didn’t knock, he just looked. The same man asked Sayin. It could be, Rid muttered. It could be worse. They followed the tracks to the knoll before the snow began to erase them. It was too late to go any further.

On the way back, the women had gathered near the fire. Tala looked scared again. Nali was with her arms crossed. Ka squeezed the same piece of seam for minutes without bending the needle. Rid went inside and put the rifle down on the table. If someone is watching, they don’t want to be seen. Paya spoke.

Still, Sayin said, crossing his arms, they don’t come for mules anymore. Re looked at each one. They don’t have to wait for me to say it. If they want to leave before spring, before it gets worse, I help them pack the car. I even accompany them to Fort Cavanok. No one moved. Ka spoke first. Let them go back to where. There is no tribe waiting for us.

The same thing happens, Paya added. Nali stepped forward. Even if we left, we would be separated again. Some would be accepted, others would not. He gave him nothing. She simply walked over to Red, took his hand, and intertwined two of her fingers with his. Reid looked at her in surprise. I don’t want to leave, he said. He held her gaze. So, don’t do it. Sayin nodded.

Me neither. The others did not speak, but it was not necessary. That night Reed double-checked the windows, placed his rifle by the door, and sharpened the old house knife he hadn’t touched in months. Sayin helped to put more wood inside. Paya blocked off the lower half of the chimney in case anyone tried to drown out the smoke. They weren’t panicking, they were preparing.

Later, when the queaceres were over and the cabin was dim again in the firelight, Reed sat down on the edge of his bed and rested his head in his hands. He breathed slowly, not out of fear, but because of the weight of it all. I had spent years without anyone in that space. Years in which the only voice was his, or the wind sneaking through the stage.

Now the room was full. Five women, each with their grief, with their strength, with their way of resisting and in some way they trusted him. Sayin quietly walked over and knelt beside him. His hand rested on his thigh giving it firmness. “You didn’t ask for this,” he said softly. Rid didn’t murmur, “but you didn’t run away from it either.

He looked at her in the firelight with his hair down. His skin still showed bruises that were erased, but now he looked stronger. More rooted is her dress, still worn and torn at the chest. It no longer looked like something broken, it looked like armor that had resisted. Sayin leaned over and kissed him. It was not rushed or for consolation. A slow, sure kiss.

When they separated, she whispered, “We stayed. If they come, we resist.” Redit passed his hand behind her neck and pulled her closer, resting his forehead against hers. He didn’t say thank you, he didn’t need it. Outside the snow was falling again, but inside they were ready, not only to endure, but to reclaim what was already theirs.

The snow finally ended in the second week of January. What was left was hard earth and mud from desire. The streams woke up under the icy crust. Steam rose from the tiles in the morning sun. The light hit differently, now, longer, clearer, pulling them towards spring. But the feeling of being watched had not gone away.

Every day after the dawn, Reed walked the path to the knoll twice, once at dawn, once before nightfall. He carried the rifle, but he never found any new footprints, no broken branches, no signs of dragging. Who had been there that day? Either he was gone or he was hiding better now. Inside the cabin the rhythm deepened. Tala was now completely healthy.

He was no longer limping. Now he was helping Pia rebuild the wall of the goat pen, nailing boards without protest. Calla was busy baking with what little flour was left, proud in silence when Rid told her that it reminded her of her mother’s bread, even if she hardly smiled. Nali, always the quietest, had begun to draw on the walls.

Small engravings, nothing noisy, just figures, symbols, soft lines with the tip of a knife. He never explained what they meant. No one asked him. Sayin stayed closer to Reed. They no longer dodged each other. At night he slept in his room. Her dress was still torn as it had been from the beginning, but now she chose not to fix it, not because she couldn’t, but because she knew he saw her as she was and never made her feel less.

He kissed her every night, sometimes slowly, sometimes long, sometimes with a quiet but cool need. They hadn’t talked about love, but it was in the way they moved around each other. in how she looked for him when her hands were cold and how he stirred his coffee before passing it to her, in how he sat closer when no one was looking with his knee barely touching hers.

It was Sayin who brought up the subject that the others probably already thought. It was late. The fire lowered his head on Rid’s chest. If spring comes and the sheriff returns, what do we answer? Red stroked her hair slowly. It depends on the question you ask. He’ll ask if we’re yours, he said bluntly. If we belong here.

Reed pondered it for a long moment. So yes. Sin sat up half covered by the blanket. Her skin warm, her eyes firm. “All of us.” His voice dropped low. Not only as workers, not only as mouths to feed. “You mean it, Rid,” he held her up. I mean it. The next morning he took the account book out of the chest under his bed.

Inside were old papers from the county Land Archives and a washed-out tampon. At the table, while the others were sewing and cleaning, he sat down and began to write. One by one he wrote down the names. Sayin Kayaali payatala. He registered them as permanent residents, registered them as family under home protection. He wrote that they were under his legal guardianship.

Not because he claimed them as possession, but because that gave them support, gave them security. He didn’t ask for permission, he just did it. When he finished, he handed the sheets to Paya. She read them, said nothing, then nodded and passed them to Calla. By nightfall, each woman had read the page with her name on it, and none of them packed their bags. The next day, Reed hitched the wagon and took the long drive to Canyon Post.

It took almost the entire day. When he returned, the pages were sealed, dated, filed, legal. By sunset they were no longer a group of strangers under one roof, they were a home. That night Sayin was waiting for him by the fire. She didn’t speak, she just got up, slowly untied the knots of her dress and entered her arms. He held her strong and secure.

He kissed her as if it were the first time. He touched it as if he had waited all his life to be elected. They made love again, this time more slowly, without fear between them. Her body was warm and full under his. His mouth opened against his skin. She didn’t rush. He guided him. It allowed him to walk through it completely, without ever straying.

When they were enveloped afterwards, still and steady under the firelight, Sinayin looked at him. “Do you know what they’re going to call us?” he said. Red kissed his bare shoulder. “Let them say so.” She smiled tiredly, but proudly. “You gave us more than a roof. You gave me more than silence.” He answered. In the corner, Tala moved in his dreams. Pia turned around in her blanket. Noli snored once. Ka muttered something in Apache and rolled on his side.

And the cabin before, a place of sorrows and ghosts, felt like home, not borrowed, not temporary, real. By the end of the week, Red knew that the one from heaven had really arrived because no one was talking about leaving anymore. They were already where they should be. Spring did not come suddenly.

He entered slowly into the smell of damp earth, into the trickle of water, down the hill, into the silent return of the birdsong at dawn. By mid-March, the snow had almost left the valley and green patches peeked out between the rocks. The hut, blackened and weathered by winter, stood firm under the open sky. The danger did not return. Wolf Hollow’s Outsider never appeared again.

There were no horsemen, there were no accusations, there were no messes, but Reid was still on the alert. Every morning I checked the line of trees, every afternoon I walked the path to the stream and back, not out of fear, out of habit, the protection was not panic, it was presence. Inside the cabin had changed in small, permanent details.

Tala hung a mobile of carved bone and rope over the window. Kaya kept herbs drying on the stove. Noli drew new symbols every week, sometimes with charcoal, sometimes with color. Paya patched the front porch and set up a handmade bench. Sain planted corn next to the shed, a row at first, then more as the ground softened. And Red smiled again.

Not big, not always, but real. Women had made space for him without asking him to change and so he changed naturally little by little. He was no longer someone who cringed when touched, or who took care of every word as if it were his last. I hadn’t expected to start a family, but now I had one, and the townspeople noticed. The rumor spread in the Canyon Post post office.

Reed Kalahan had received five Apache widows. No one knew if it was out of compassion, marriage, or scandal. But in April the gossip died down because when the notary went to check routinely and found the cabin he cleaned the papers in order to the women working the land and smiling at the man who had inscribed their names with respect.

There was nothing to say, no broken law, only silence. One afternoon, under a soft orange sky, Rid went out behind the cabin where Sayin was rinsing clothes in a bathtub. Her hands wet, her dress stuck to her hips. She looked over his shoulder as he approached. Then it dried on her skirt. “You breathe heavily,” he said.

“I was carrying stones,” he replied. You sound like an old man. “I’m an old man,” he said smiling. She cocked her head, narrowing her eyes. Not so old. He took a step closer. I want to ask you something. She crossed her arms. You can’t ask me to leave now. It’s too late for that. He shook his head.

I want you to marry me. She stared at him, without surprise, not smiling yet. This is by law, he asked. It’s not to keep others away. No. She studied his face. So why did Red swallow? Because you’re the strongest person I’ve ever met. Because when I wake up the first thing I look for is you.

Because when I think about what I want 10 winters from now, it’s this, all this, you, this home, this life. Sayin let out the air slowly. His hands fell to his sides, he took a step and rested his forehead on his chest. He felt his fingers cling to his shirt. “I never thought of belonging to anyone again,” he whispered. But I’ll be yours.

Rid kissed the top of his head. Only if you want to. “I want to,” she said, “but I won’t wear white.” He laughed softly. I didn’t ask you. “Well,” she answered, “because I don’t intend to change this dress either.” He turned away and looked at him mischievously, still broken as he is. He looked at her bare shoulder, the tear in her chest, the glitter of her skin under the sun and the water. I wouldn’t want you with anything else, he said.

They were married under the fir tree behind the hut two days later, without a priest, without an audience, just them and the others watching. Pia stood by Sayin’s side, arms crossed, but smiling. Ka held the braid that Sayin had woven into her own hair. Apache tradition passed down from woman to woman. He didn’t engrave a small symbol on the tree, a permanent attached circle.

Tala brought wild flowers from the hill and laid them at his feet. Red said a single sentence: “You stay with me and I stay with you.” Sayin replied, “Then we stayed and that was enough. The sun warmed them, the earth accepted them, the wind moved, but it took nothing.

That night, as dusk fell on Silverbot and the goats fell silent, Reed sat on the porch with Sayin on his lap, his back against his chest. The others were laughing inside, someone maybe Nolly was singing. A soft, unknown melody. Sinin’s hand rested on his belly. Re noticed it, but still didn’t ask. She turned her head. In a few months, she said, he held her tighter. You’re scared, she shook her head.

Not anymore. Re looked out over the field where the corn was barely sprouting. They won’t understand, he murmured. Sayin smiled. They don’t have to. And they remained silent. Two people who had lost everything, but found the one thing that was worth more. They stayed. And that was love, that was the end, that was home.

News

I spent the night with an unknown man at the age of 60, and the next morning the truth left me in shock…

I never thought that at 60 years old something so strange would happen in my life. A woman who had always been prudent, who had lived by the rules, devoted her whole life to her family, husband, and children… Suddenly…

The 2-year-old baby kept pointing to his father’s coffin and crying inconsolably. What happened next was horrifying…

It was a gray Saturday afternoon when Emily Thompson stood on the edge of the grave, her heart broken by loss. The air was heavy with pain and the sky seemed to weep with her, with dark clouds hanging low. Mark Thompson, her…

He laughed as he signed the divorce papers—but the judge’s reading of my father’s will changed everything…

The courtroom smelled faintly of coffee and disinfectant, a mixture that did little to calm my nerves. My name is Emily Carter, and today was the day my marriage to Daniel Parker would be officially dissolved. Four years of betrayal, manipulation and mockery…

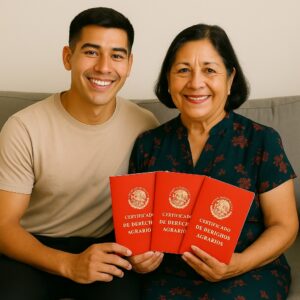

On the wedding night she put in my hands 3 land deeds and the keys to a Porsche valued at 6 million pesos, but when I lifted her dress I was frozen…

I’m Luis, I just turned 20, I’m 1.80 meters tall, I have a nice appearance and I’m a sophomore at a university in Mexico City. My life was pretty normal, until I met Doña Carmen—a wealthy 60-year-old woman who had owned a chain…

The Mother Who Left in 1990 – And the Secret Revealed After 35 Years

1. The Wound from Childhood In 1990, our quiet little village was shaken by shocking news: my mother—the gentle, hardworking woman who had raised me alone—suddenly left with the wealthiest man in the region. On our rickety wooden table, she…

My mother-in-law has no pension, I have taken care of her wholeheartedly for 12 years. With his last breath, he held out a broken pillow and said: “For Mary.” When I opened it, I was in tears…

My Father-in-Law Without a Pension, I Cared for Her Wholeheartedly for 12 Years. With Her Last Breath, She Handed Over a Broken Pillow and Said: “For Maria.” When I Opened It, I Wept Right Away… I am Maria, I entered…

End of content

No more pages to load